Natural Environmental Change: Extreme Climate Events and Groundwater in East Africa

East Africa has some of the most highly variable topography in Africa. Ranging from vast plains to highly mountainous areas, the topography of the area is ideal, with its excellent ecological and climatic archives, for climate and environmental studies. More importantly, some of the lakes located in the area are known as amplifier lakes as even little climatic changes have a big impact on them. The Central Kenya Rift and the Tanzania Rift located in East Africa contains some of these amplifier lakes, sometimes called small soda lakes, such as Elmenteita and freshwater lake Naivasha. Climate, tectonically driven morphological and volcanic barriers, and local water-table variation all influence the hydrology of this region. Moreover, the groundwater held at the two rifts counts for much of the area’s human and industrial usage, making the hydrology of the area particularly important. However, over the last 150 years, the rapid change in climate and natural environment, such as the 2015/16 El Niño event discussed in this post, has been more severe than before, causing changes in precipitation patterns.

Groundwater

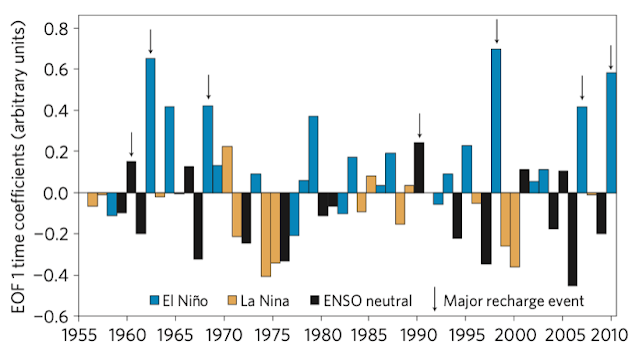

Figure 1. Time series of the leading EOF of regional monsoon season precipitation in East Africa.

Figure 1 presents the study by Taylor et al, indicating time series of empirical orthogonal function (EOF) of regional monsoon season precipitation in East Africa. With demonstrations of El Niño, La Nina, ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) and major recharge events on the graph, we can see that major recharge events are in correlation with major El Niño events.

It is commonly recognised that groundwater recharge results from effective precipitation, that is when evapotranspiration was loosed from precipitation, infiltrating the subsurface where hydraulic gradients are downward. Nevertheless, due to a shortage of long-term observational data, the link between precipitation and groundwater recharge remains unclear and ambiguous in many places. This can be attributed to the uncertainty of soil infiltration capacities under the real-life heavy rainfall scenario. The main way of groundwater recharge in semi-arid environments is the focused

The 2015/16 El Niño and East Africa: Kenya

The 2015/16 El Niño has been recognised as one of the three most severe on record, causing droughts in southern Africa and intense precipitation in eastern Africa. Hydrological effects are especially highlighted in East Africa because of the complex environmental and socioeconomic consequences that extreme rainfall can cause.

Figure 2. The amount of precipitation in Kenya, 1997 and 2015

However, Kenya’s 2015/16 El Niño, in comparison with the 1997/1998 El Niño which have greater precipitation and caused more damage (Figure 2), presented not only unexpected milder precipitation but also suggested the importance of a country’s adaptive, region-specific management strategies to extreme events.

In December 2015, the International Red Cross reported 113 death and 103,000 displaced; however, this tragic event was described as “incomparable” to the 1997/1998 El Niño where “everyone was a victim”. The incident of 1997/1998 El Niño has left an indelible mark on institutional memory, and as a result, flood danger is well-known. A high degree of national readiness for El Niño across the board was seen: stakeholders including the government, the commercial sector, communities, and even individuals are fully involved. For example, the establishment of institutions such as the National Disaster Operation Centre (NDOP) has helped in monitoring and communicating risks. Activities like the allocation of funds, drain cleaning and numerous plant and animal protection initiatives have all contributed to the eventual mild scale of disruption in 2015/16.

Reviewing the impact of extreme climate events like El Niño on groundwater in the East Africa region and drawing specific cases to look at Kenya, we can see the importance of having an improved understanding of hydrological responses in making adaptation management strategies.

El Niño and La Nina have been two terminologies that i have heard since I was a child. However I rarely had the chance to investigate them in depth. I felt well informed with this post's detailed explanations and I started to see how these climate phenomena are impacting people's life directly. I started to recognise how an effective hydrological response is of paramount importance.

ReplyDelete